Theatre critics never mention the cost of a ticket when we write our reviews, almost as if price doesn’t matter and the aesthetics of theatre operate independent of budget and cost. Maybe that’s because we critics don’t pay for tickets, so we never leave a show saying: “I just paid $102 for that! I’d have enjoyed myself more at my child’s Nutcracker or my Great Aunt Nelly’s piano recital!”

Theatre critics never mention the cost of a ticket when we write our reviews, almost as if price doesn’t matter and the aesthetics of theatre operate independent of budget and cost. Maybe that’s because we critics don’t pay for tickets, so we never leave a show saying: “I just paid $102 for that! I’d have enjoyed myself more at my child’s Nutcracker or my Great Aunt Nelly’s piano recital!”

The reality is, of course, buying the opportunity to experience a theatrical production is no different than buying a bottle of wine. If I were to shell out $232,692 for a bottle Chateau Lafite (1869) or even $80,000 for a Screaming Eagle Cab (1994) – yes, those really are the latest prices for those wines – it had better have a darn good bouquet and a taste that lasts forever. Whereas, if I go to my local Safeway and buy a Clos Du Bois Chardonnay for $10.99 or a bottle of Three Wishes Chardonnay for $2.99 at Whole Foods, I only expect to relax and enjoy myself a little without a bitter aftertaste. In my youth, a bottle of Boones Farm served one purpose and one purpose only, and it did not have a thing to do with aesthetics.

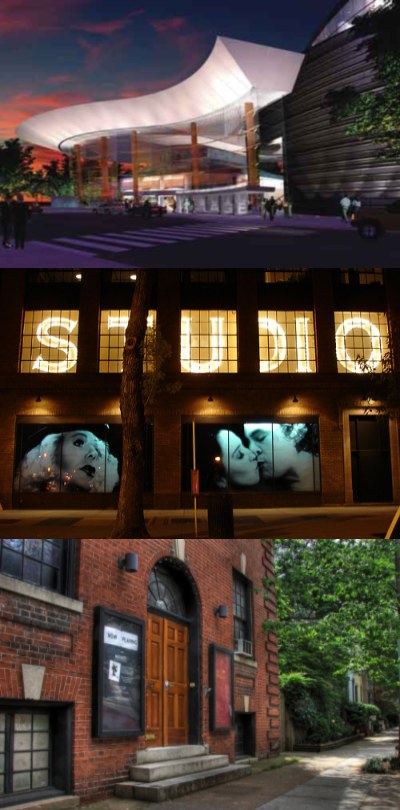

So let us be honest: when it comes to theatre, price matters. If we pay more for a theatre ticket, we expect more from the show. Top prices at Arena Stage and Shakespeare Theatre are now over one hundred dollars a ticket, whereas at the National Theatre a single ticket approaches $200. Studio Theatre and Woolly Mammoth, on the other hand, charge a mere $60 to $75, whereas a company like Avant Bard (WSC) or a Fall Fringe production charge $30ish and $20ish respectively. Now, we can all admit that when we walk through the doors at Arena or Studio, our expectations are different (and higher) than when we slide into a cheap seat at the Fringe.

The question remains, however, what exactly are theatre-goers expecting for that higher price? I guess the simple answer is: the best that money can buy. I do not know what the exact relationship is between a theatre’s budget and its ticket prices; but generally it seems that the more money a theatre has, through charitable donations, grants, and box office, the more money it has to spend on its productions and the more it charges for its tickets.

So the essential question is: when it comes to theatre, what does all that money buy?

A hot script to be sure. Whereas theatres with fewer resources must rely on tried and true scripts, or obscure risky scripts, or newly invented original scripts, the wealthier theatres can afford to get the rights to that latest gem or enduring blockbuster.

The bigger the budget, the more famous an actor the theatre can hire. How many theatres in Washington could afford the likes of a Stacy Keach or a Cate Blanchett or a Laurence Fishburne or a—you get the picture. A big name doesn’t guarantee expectations being met, but it frequently covers the bet.

If not the big name actor, then a bigger budget ensures a higher quality ensemble—or both. Yes, money definitely opens the door to a plethora of quality actors with more training and experience.

More extraordinary sets and beautiful costumes also cost more. If you are going to witness a helicopter flying around on stage, or a large set piece descending from the sky, or an even larger set piece emerging from the floor, ticket prices have to be higher than a dinner at Applebees.

The richer the theatre, the more luxurious the theatre experience. Now, this expectation might be more true of Washington than any other city in America because Washingtonians, who have grown used to the comforts of government largess, expect no less from their entertainments. Thus, theatre lobbies need to be large and well equipped, guaranteeing that a production’s half time show is not a cigarette in a dark alley.

The costlier the ticket, the richer the audience. As prices escalate, the professional theatrical experience becomes increasingly limited to a wealthier and wealthier clientele. Of course, theatre managers understand this fact; hence, theatres offer a host of reduced-priced ticket opportunities, from Ticketplace to Living Social to Goldstar to discounts for theatre-goers 35 and under to Pay-What-You-Can nights.

Ultimately, however, more theatrical money produces a more monied aesthetic. For, to be sure, money brings with it its own idea of beauty. If we set aside the creative factor—which I never like to do by the way, but let’s set it aside this once—money in theatre, like money in politics, can make a dull idea look interesting and bright and thought provoking and thus a joy to behold. In other words, that expensive look, supported in part by those high-ticket prices, can gloss over an Everest of “been theres, done thats, so who cares?”

I don’t know if we critics ought to start mentioning the price of admission when reviewing a show. Saying, “For $25, it ain’t a bad show!” doesn’t really sound like an endorsement; but a ticket’s price should at least filter into the equation, as it already does for many theatre-goers or would-be-theatre-goers who then decide to save that $100 bucks for their kid’s college fund. And I say that even though I know that money cannot make a show worth seeing or memorable. Creativity and empathy do that! It’s the story that does that! So remember, while some of the most creative and most empathetic people don’t make squat for their artistic labor, they can be found at theatres anywhere and at any time.

In this season of spending and economic uncertainty, as you wrestle with which holiday show you want the family to see, I’m sure you’ll consider the price tag of that Nutcracker or Christmas Carol. Rest assured, that if you go for the lower priced Tiny Tim, no one will consider you a Scrooge for doing so.